Raise your hand if you’re a Millennial. Or, maybe not. There’s a good chance you identify more with one of the chromosome generations (X and Y).

For market researchers and others, there’s no consensus about the start and end of birth years for each generational label. To make it even more complicated, most Millennials don’t even want to hear the “M” word.

The Genesis of Generation Labeling

If you’re looking for people to blame for the often-confusing generational tags, look no further than William Strauss and Neil Howe. They pioneered the concept of generational cycles and coined the term Millennials in their seminal 1991 book, Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069.

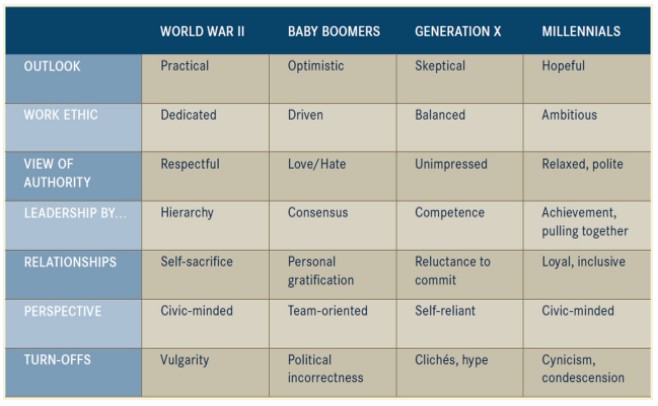

Strauss and Howe theorized that people who grow up under similar circumstances often share the same characteristics relating to attitudes and behaviors such as work ethic, respect for authority, spending habits, technology adoption, and patience. If you’re a Baby Boomer, you’ll act one way. But if you’re a Millennial, you’ll behave differently. Well, that’s the idea anyway.

Bundling generations into 20-year buckets is a handy way for social scientists and marketers to understand how to reach potential customers. From product development to pricing strategy, and from sales tactics to media planning, generational labels have proven to be effective marketing tools.

Here’s a look at how Augusta University views the behavior differences between generations:

But here’s the challenge: There’s significant disagreement about who’s in what generation, and even what they’re called.

No Consensus from the Census

One of the problems with generational labels is there’s no overriding authority to determine birth years or labels.

Philip Bump, writing for The Atlantic, contacted the expert in demographic data: The U.S. Census Bureau. He was told, “We do not define the different generations. The only generation we do define is Baby Boomers, and that year bracket is from 1946 to 1964.”

Without a heavy governmental hand, the result has been a free-for-all, with several expert wannabes jockeying to become the generational label authority. It’s true that most sources acknowledge the postwar years 1946-1964 as Baby Boomers. But outside of that, forget it.

For example, the years before 1946 (from roughly the mid ‘20s) have a different label depending on who you ask. The Center for Generational Kinetics calls them Traditionalists. Wikipedia refers to them as the Silent Generation. And The WJ Schroer Company tags them as Post-War Cohort. Take your pick.

There’s a strong consensus that post-Boomers are called Generation X, with the bracket’s birth year beginning in 1965. It’s end-year date is more fluid. The Harvard Center sets it at 1984, but Nielsen Media Research prefers 1979.

The Millennial Riddle

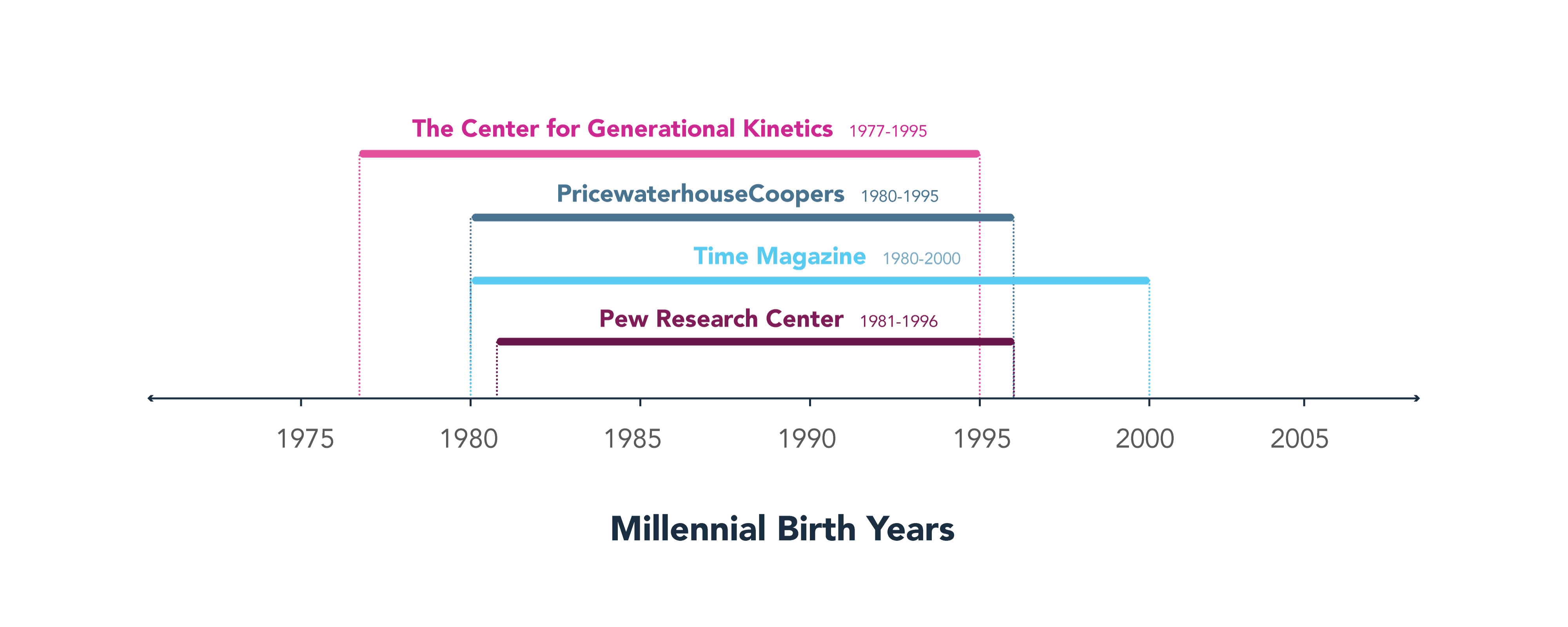

Labeling Millennials is where this really gets tricky. Here’s a look at how various entities define the generation’s birth years.

According to Pew Research Center President Michael Dimock, as quoted in Dante Ciampaglia’s Newsweek article, “What is a Millennial?,” “generational cutoff points aren’t an exact science.”

Pew settled on 1981-1996 based on a few key criteria: from their understanding of the “historical significance” of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, to their role in sending Barack Obama to the White House in 2008, to their comfort and adaptability when it comes to technology.

“Most millennials came of age and entered the workforce facing the height of an economic recession,” which led to a decline in earnings and a necessary putting off of important landmarks, Dimock continues. “The long-term effects of this ‘slow start’ for Millennials will be a factor in American society for decades.”

Deciding who is and isn’t a Millennial gets more muddled when some marketers use Generation Y, instead, including The Harvard Center and The WJ Schroer Company. Hey, that’s a great idea. Let’s call the same thing by two different names.

And while we’re at it, let’s make things even more crazy.

Kasasa, a financial technology services company, eschews both the Millennial and Generation Y terms. Instead, they’ve divided the generations into two new categories:

- Generation Y.1: 1980-1990

- Generation Y.2: 1990-1994

According to Kasasa and Javelin Research, “Not only are the two groups culturally different, but they’re in vastly different phases of their financial life. The younger group are financial fledglings, just flexing their buying power. The latter group has a credit history, may have their first mortgage and are raising toddlers. The contrast in priorities and needs are vast.”

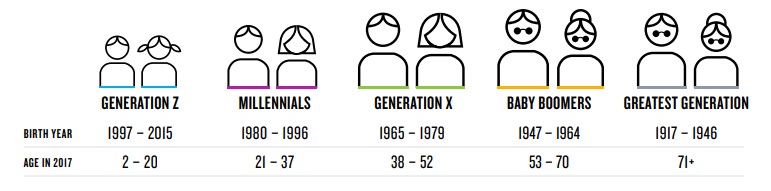

It’s perhaps best to keep things simple. At Zion & Zion, our market research team likes the way Nielsen divides the generations:

The Millennial Myth

Generational labels have also been used as derogatory identifiers, especially when it comes to being a Millennial. Ciampaglia put it well: “Older folks have loaded the term with so many negative stereotypes. Millennials are coddled; Millennials are entitled, Millennials are snowflakes. (All of that’s generation-war propaganda, by the way.) But like most generational tags, the boundaries of Millennial-dom are fungible based on who’s defining the term.”

Such stereotypes have led to a cottage industry of drawing caricatures of Millennials and other generations. Here’s two videos that make the point.

Those videos are funny, biting, and certainly exaggerate generational differences. But, such stereotypes may be more myth than fact.

Simon Sinek—author of Start with Why and whose same-titled Ted talk on YouTube has garnered 4.4 million views—has helped spread what’s been called the Millennial Myth. Here’s what he said on Inside Quest:

“Millennials are unmanageable in corporations because they are impatient, lazy and entitled as a result of bad parenting, addiction to cellphones and Facebook depression. However, it’s not the Millennials fault. They were dealt a bad hand. The solution is for corporations to parent Millennials by adding “parenting” as a bullet point to the corporate responsibility charter. This solution requires corporations to hire a new age management consultant to teach middle managers how to parent new hirelings.”

The thing is, Sinek may not be right. A study by Bankrate.com found that Millennials are actually less entitled than Baby Boomers. According to the study, Millennials believe in financial independence—owning a home, and paying for your own car and mobile phone contract—a year and half earlier than Baby Boomers.

Rejecting Generational Labels

Confusing birth ranges, a myriad of labels, and unflattering stereotypes have led to an interesting phenomenon: Millennials don’t want to be called the “M” word. And by a wide margin. Other generations don’t appreciate being pigeonholed, either.

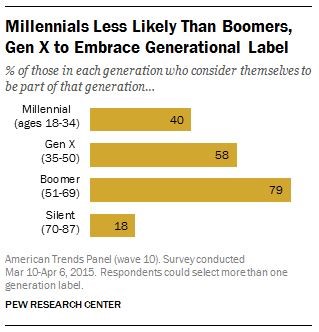

A 2015 study by Pew Research Center found that a convincing majority of Millennials don’t identify with the term. Only 40% of people who would normally be classified as being a Millennial consider themselves a part of the “Millennial generation.” The study also found that “another 33%—mostly older Millennials—consider themselves part of the next older cohort, Generation X.” Other generations express similar label rejection, although but not as much.

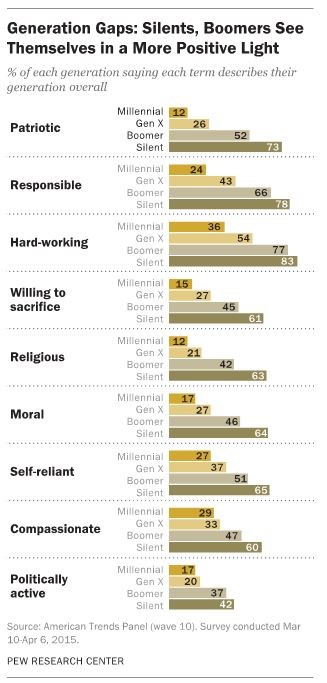

Despite label rejections, the Pew study found that generations do indeed evaluate themselves as being different than others. Millennials are particularly hard on themselves. One glance at this graph makes it clear that Millennials believe they are less patriotic, responsible, religious, and hard-working than other generations. In fact, Millennials ranked themselves lowest in every category.

Talkin’ ‘Bout My Generation

The market researchers, strategy experts, and media planners at Zion & Zion simply stay focused on what’s important—not obsessing about what to call people, but by discovering what they think (through practices such an empathy interviews, associated with Design Thinking) and how to motivate them to engage with our clients’ brands.