The Challenge

Goodwill of Central and Northern Arizona is the largest Goodwill organization in the country. The client operates 84 retail stores, 20 donation centers, 3 clearance outlets, 3 furniture stores, and 20 career centers and has revenues nearing $150 million.

Zion & Zion has served as the client’s Agency of Record for the past several years.

The challenge was twofold:

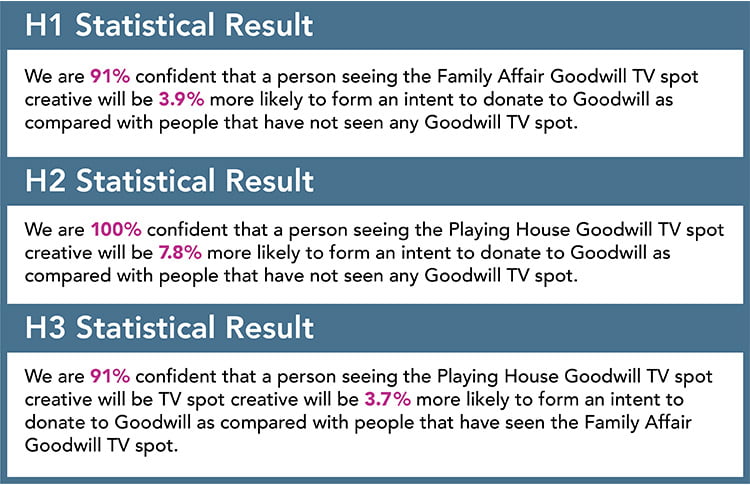

- Confirm that both of the two TV commercials we developed for Goodwill will have an impact on people’s intention to donate items to Goodwill

- Determine which of the two TV commercials will have the greatest impact on people’s intent to donate goods