What is IA?

Information Architecture (IA) has been around for almost as long as the internet has been around. While it may not have had a name quite yet, early developers considered basic IA principles when building their sites. As with most terms used in web design, the definition of information architecture has grown with the industry, and as a result of this, there are many different definitions of information architecture floating around the web.

I like to refer back to the definition that Louis Rosenfeld and Peter Morville, the authors of the O’reilly book /Information Architecture for the World Wide Web, created. The pair define information architecture as:

“The combination of organization, labeling, and navigation schemes within an information system.”

While I like this definition, I consider it more of a “textbook definition,” one that someone who is not in the field may have to read a couple times to fully comprehend. It’s thorough and a good base definition, but I prefer a second definition of theirs:

“The art and science of structuring and classifying web sites and intranets to help people find and manage information.”

Not only is this definition easy for everyone to understand, I love that they classify information architecture as both an art and a science. This is what I enjoy so much about my field. Organizing the information is a science because you work with data principles and psychology to create user paths. But it’s also an art; you have to be imaginative and creative to connect with your users.

Components of Information Architecture

Rosenfeld and Morville also developed four components of IA that help to define what information architecture really is.

Organization Systems

Organization systems refer to how you group and categorize information to help users find what they need. This can be done through organization schemes or organization structures. Organization schemes are how you categorize the information: for example, alphabetically, chronologically, by topic, or by audience type. Organization structures refer to how you group and connect the information.

Two of the most common types of organization structures are:

- Hierarchical (parent level pages with children pages)

- Sequential (step by step)

The way you group and categorize your content helps your users to quickly find the information they need.

Labeling Systems

The second component of IA is labeling systems, which refers to how you name the information. There are many different approaches to how to properly label your navigation and content. However, the bottom line is that you need to identify a label that accurately describes the content it contains. The label needs to be something that your users can understand and anticipate what the content behind that label will be.

Navigation Systems

Navigation systems refer to how users can navigate through your site. Whether your site has a global navigation (a navigation that is consistent from page to page) or local navigation (a navigation for a sub-set of pages), you need to plan how your users can, should, and will navigate from page to page to access the content that they need.

Search Systems

I often think of search as the user’s last resort to find your information, but tests show that many users rely on search as their first approach to finding content. However your users interact with search, it’s important to plan out how they find the content they search for. Using functionality like predictive search, for example, helps to guide users to the content that they’re searching for.

Creating an Information Architecture

Now that you have a good understanding of what an IA is, I’ll walk you through how to create one.

Step 1: Research

Users

Understanding your users is key to creating a successful IA. Through interviews, surveys, and creating personas you can learn what your users want, the language they use, and how they interact with sites. Truly knowing your users will help you to label, organize, and structure the information in a way that your users will understand.

Competitors

Understanding how your competitors organize and label their IA is important so that you can understand what you’re up against. When your users are doing research online and are comparing you to a competitor, they’ll likely pick the site where they can easily find the information they’re looking for. If your site has a worse IA than your competitor, you may be losing business.

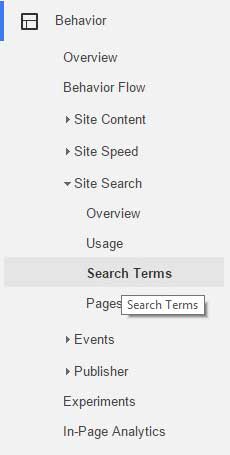

Analytics

If you’re re-building your site, it’s important to research how your current site is performing before deciding on an IA for the new site. One of my favorite things to look at is the on-site search report in Google Analytics. This shows what people search for using the search on your site. If there’s a term being searched for often, it probably means users are having a hard time finding that content—and you should reconsider how it’s labeled and/or organized.

You can find this report in Google Analytics under Behavior > Site Search > Search Terms.

Step 2: Plan

Card Sorting

Card sorting is a great way to begin the process of organizing and labeling your information. We use Optimal Sort’s online card sorting, which I recommend. It allows you to create labels and drag and drop them into groups, so you can quickly visualize the organization. It also allows you to send it out to other people to see how they would organize and label the same information, which we have found extremely helpful.

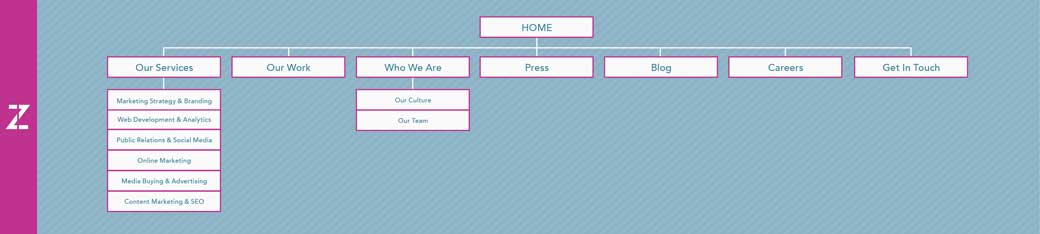

Sitemaps

Sitemaps show the hierarchy of the pages on the site. A sitemap visually shows the parent pages, children pages, and how each page relates to the other. Building these during the planning stage helps me to visually see all the pages on the site to ensure I haven’t missed anything. It doesn’t, however, show the flow that a user can take from page to page—queue in user flows!

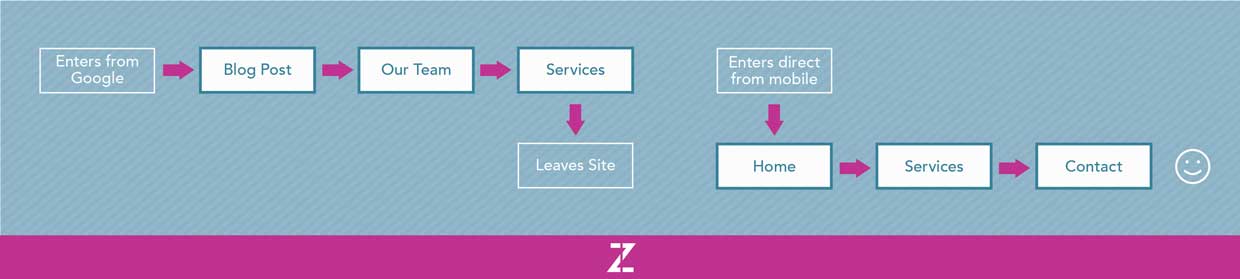

User Flow Diagram

User flow diagrams show the path that a user can take through a site. This needs to be planned out well to ensure that your different user types can navigate through the site easily to get to the information they need. Since a user may visit the site on their desktop, navigate around, then leave the site and enter later on their smart phone, this wouldn’t be shown in a sitemap.

A sitemap and a user flow diagram work together to help us plan how the information needs to be organized and grouped.

Step 3: Test & Perfect

Testing

While you may think that you’ve created the perfect IA, you won’t know how successful it’ll be until you test it. If you have access to your real users, this is the ideal situation. Watch them as they navigate through the site. Give them tasks to complete and watch as they do them. If you can’t access your real users, you can use online tools like Usertesting.com or Usability Hub to watch users who fit into your user demographic complete tasks on your site.

Analyze, Update & Test Again

Review the results of your user testing and make the appropriate changes, but don’t stop there! Test the updated site again to ensure that it performs better than before. Repeat this step as many times as necessary until you’ve found the ideal IA.

What makes a successful Information Architecture?

You should now have an IA that will work well for you and your users! If the IA is successful, the user will not only have zero issues finding the information they need, but they won’t even need to consider how they got the information. In other words, a good IA should be so intuitive that the user didn’t even need to second guess the steps they took to find that information.

A good information architect is like a good plastic surgeon—if they succeed at their job, their work goes unnoticed.

It’s an interesting thing to hope that a user doesn’t notice the hard work you’ve put into a project, but I’m sure plastic surgeons feel my pain.

So what makes an IA so intuitive? Here’s my checklist of five things my IAs must always be to ensure they’re easy to use. I keep these in mind as I’m planning and building, and then when I’m done with a project I run back through this checklist:

Visible

All navigation items, call-outs, and buttons must be visible for all users. Consider the varying ages and abilities of users, as well as the varying screen sizes and devices.

Consistent

Navigation must be consistent from page to page.

Comprehensive (yet concise)

Navigation labels and buttons must give users enough information, without overwhelming them. Always consider if labels can be said in fewer words and still get the information across.

Predictable

Users should be able to easily predict where a button or label will take them.

Built for the users

It always comes back to the user. The structure must follow the user’s thought process and language.

Evolution

After testing, analyzing, updating, repeating, and ensuring you’ve built a successful IA, you’d like to think you’re done, right? Not quite. As information architects, our job is never truly done!

Once the site has launched and real users are interacting with the site, continue to monitor how it’s performing. Are you finding that users are still using the in-site search for something that you thought was easy to find? If so, it’s time to make some slight adjustments to make your site as easy to use as possible. At Zion & Zion, we like to think of the web process as an evolution. We’re always adjusting and perfecting to improve our work!