The last principle we’re covering within our series on user experience and email design is scarcity. When implemented correctly, scarcity can be extremely persuasive in influencing users to be drawn to limited items or items out of reach. Specifically, when applied to email design, this principle can help you form the foundation of an influential and effective campaign.

If you haven’t read the previous articles within this series and want more context to the principles of persuasion, we recommend beginning at article one.

Understanding Cialdini’s Sixth Principle of Persuasion: Scarcity

Within this article, we’re diving deep into the sixth principle of persuasion, scarcity. Scarcity can be defined as the following:

If something is less available to us, we want it more.

Read on as we cover what scarcity is, how it’s been proven, what examples support the principle, and how you use this principle to your advantage in your email campaigns.

What is the Scarcity Principle?

Hurry! The information within this article expires tonight!

Just kidding. But that made you want to read this article even more—it’s the power of scarcity. Once something becomes less available, achievable, or reachable to us, we’re driven to want the item that much more.

Scarcity works well because it restricts our freedom and choice, which is something we never want to bare. We hate to lose the freedoms we already have. That’s why, when faced with a limitation on something we desire, or even something we didn’t want in the first place, our response is outright defiance. We’ll do everything we can to reach that unachievable goal, or purchase that now desirable product.

The logic behind this principle shows how powerful scarcity can be, and how much more persuasive your email design can be when this social tool is implemented correctly.

The Proof

The principle of scarcity has been researched, tested, observed, and most importantly, proven many times throughout the years by experienced psychologists. However, for our discussion today, we’ve chosen to feature one of the most noteworthy studies, the terrible twos study.

The Terrible Twos Study

One prominent study that effectively demonstrates the principle of scarcity is the terrible twos study. The terrible twos study was based in Virginia. The purpose of the study was to observe and evaluate the behavior of a handful of two-year old boys in two distinct scenarios.

In both scenarios, the young boys were given a choice between two equally desirable toys. These toys were of the exact same value as one another and were put in front of the children at equal distances away.

In the first scenario, one toy had a barrier in front of it and the other toy was left out in the open. The barrier was made of plexiglass, so the boys could see the toy. In addition, the barrier was one-foot high, which made the barrier no real barrier at all, as it was short enough for the subjects to reach over. After observing the actions within this first scenario, it was clear that the two-year-old boys had no real preference as to which toy they favored.

The second scenario had a slight variation. Within the second scenario, participants were asked to choose between two toys. These toys were still of equal value and were still placed at equal distances in front of the boys. One toy was left in the open and one toy was behind a plexiglass barrier. However, this time, instead of creating a barrier the children could easily reach over, the experimenters raised the height of the barrier so that it stood two-feet tall. This taller plexiglass created a true barrier for the toy, as it was too tall for the participants to reach over.

Within the second scenario, the experimenters found that an overwhelming number of participants wanted the toy that was being blockaded by the plexiglass, the toy that they couldn’t reach. In fact, the toy located behind the barrier was grabbed three times faster than the toy that was within reach.

These results had nothing to do with which toy was best. Rather, the results were entirely dependent on the accessibility of the toy. When the toy was out of reach, the children wanted it more. This is due to the principle of scarcity—if something is less available to us, we want it more.

The Support

Now we’ll move onto the support of this principle. We’ll do this by covering three strong examples of scarcity within email design.

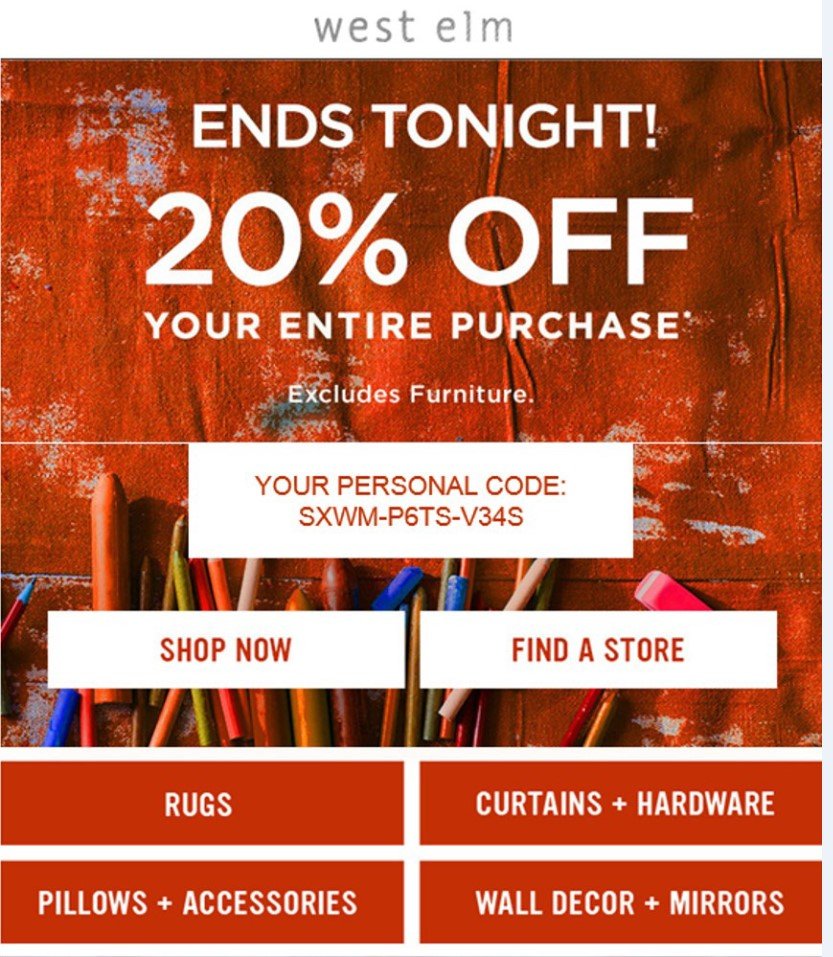

West Elm

The first email example we’re sharing on the principle of scarcity is by West Elm. West Elm is an ecommerce company that sells a wide range of interior décor pieces. Specifically, within this email, West Elm is using the principle of scarcity to encourage users to purchase a product.

This principle is evident through the headline that reads “Ends tonight! 20% off your entire purchase.” By featuring the “ends tonight” verbiage, the company hints that the offer will soon be unobtainable. This works to make the user want it even more.

Because there’s a time constraint on the offer, email becomes more influential and more effective in drawing customers to purchase a product. However, imagine if West Elm sent this email every day. The first time the user receives an email with the verbiage “ends tonight,” they’ll feel eager and excited, as the offer would feel scarce. However, the next time the user receives the “ends tonight” email, the offer would feel less desirable. And the next time, it would feel even less desirable than the time before. This is because the user would grow accustomed to the offer, making it is less scarce.

At Zion & Zion, we recommend limiting the amount of time you implement the principle of scarcity throughout your emails, and throughout all your marketing efforts. When you overuse scarcity, the effect of the principle wears off, counteracting the persuasive element of this tool.

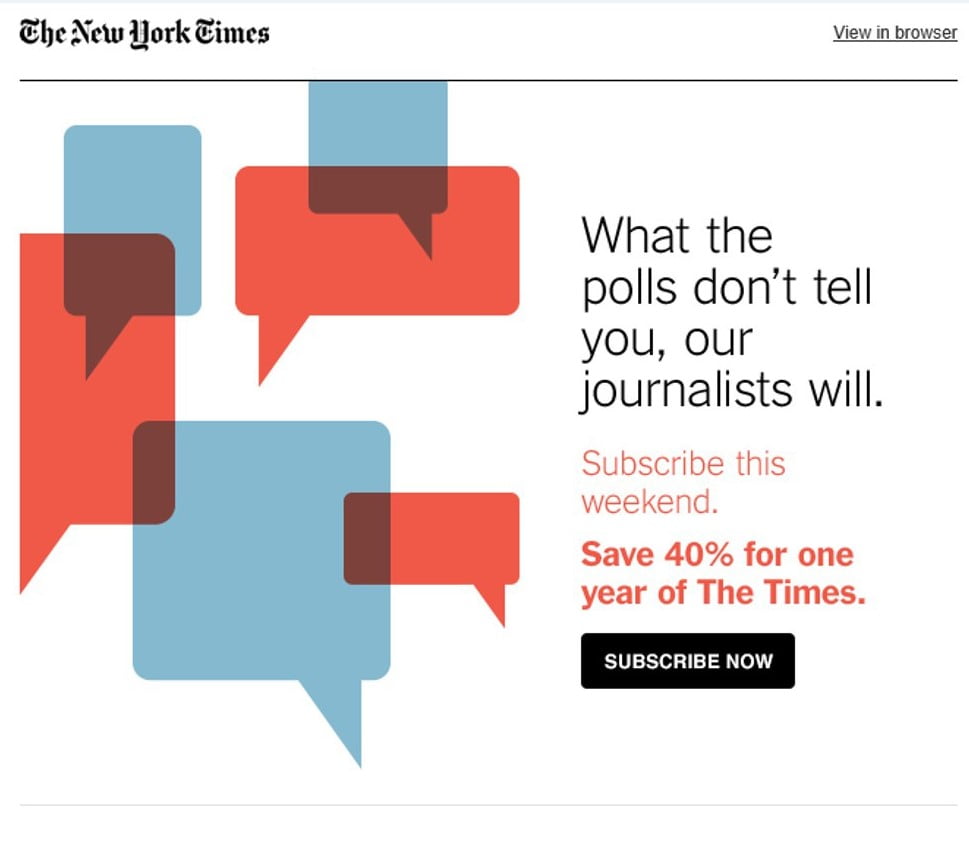

The New York Times

In the previous example with West Elm, we showed one of the most popular ways to use scarcity, by pushing limited time offers to sell products. However, we wanted to provide a different example to show that scarcity can also be used in other strategic and effective ways, without the use of an offer. (Psst! If your company can’t easily discount your products or services, this example is for you.)

The below email, sent out by The New York Times, uses the principle of scarcity in a unique way. Specifically, the copy reads “What the polls don’t tell you, our journalists will. Subscribe this weekend.”

This email works well because it uses scarcity without forcing a rigid time limit. For instance, the company transformed the typical scarcity verbiage of “Hurry! Offer ends in 48 hours!” to a gentle tone, reading “Subscribe this weekend.” This change in tone helps to create a less intense environment, while still successfully leveraging elements of scarcity.

In addition, this email differs from the previous example because instead of discounting a product or service, the company chose to leverage valuable and timely information. Creating timely resources, pamphlets, white papers, and other information on your company is a great way to leverage scarcity if you don’t have the means necessary to discount your actual products or services.

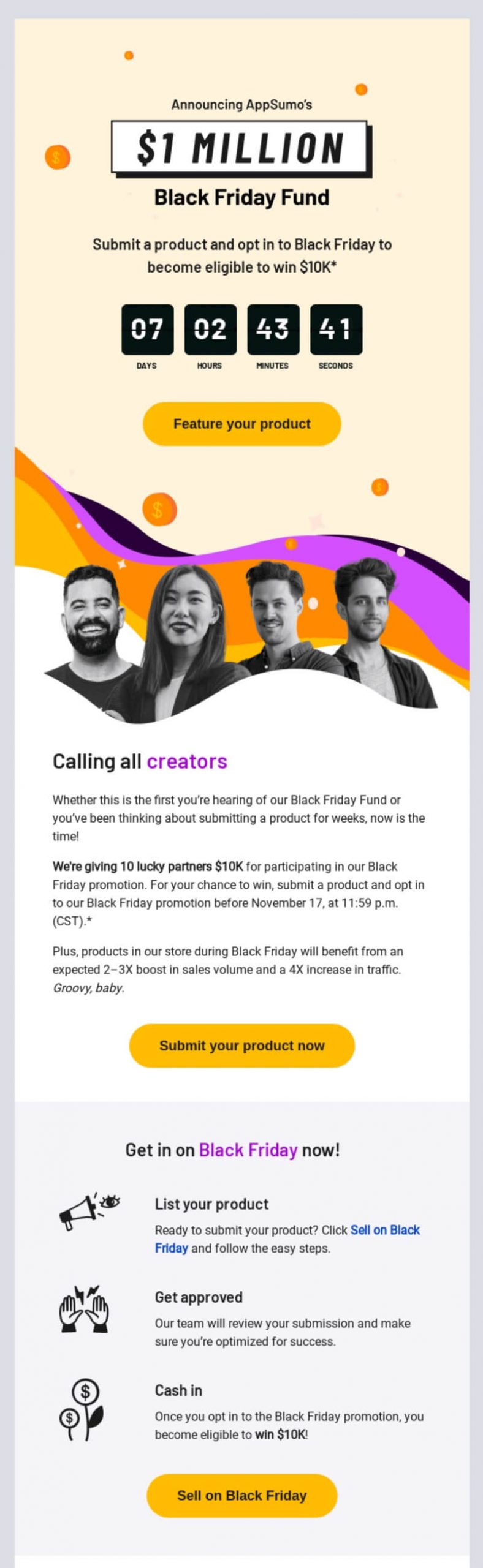

AppSumo

The final example we have the embodies the principle of scarcity was sent by AppSumo. The email instantly captures the recipient’s attention by featuring a prominently displayed countdown timer in the header. This strategic use of a ticking clock effectively instills a sense of urgency within the recipients. It conveys that time is of the essence, and a valuable opportunity is slipping away. In doing so, AppSumo taps into the psychological trigger of scarcity, compelling the recipients to take immediate action.

This skillful implementation of the scarcity principle goes beyond just being visually impactful; it plays on our natural inclination to desire what is limited or about to disappear. It’s a powerful technique that not only drives engagement but also underscores the exceptional value of the offer at hand.

The Application

When applying scarcity to email design, ensure you’re being strategic about when and how you use this principle. Overusing scarcity can lead to an expected, uninfluential, and unsuccessful email design.

However, if you use scarcity strategically for your offers, products, services, or even information, this social psychological principle will help you create an effective campaign.

Wrapping Things Up

In this series, we discussed how you can use Robert Cialdini’s’ six principles of persuasion to produce UX-friendly, persuasive email marketing / marketing automation campaigns.

Remember, when implementing these principles into your emails, be deliberate about which principle you want to feature, in what order, and why. You don’t necessarily need to implement all the principles into one email, nor should you. Instead, think in terms of your user. Test the elements in your emails. Analyze the results. Make changes based on your findings. These tactics will help you narrow down which principles work best in nurturing long-term relationships with your users.

For further practice, use the below checklist to help you implement the principles of persuasion across your email campaigns. Strive to have at least one principle per email. Feel free to use our suggestions or write in your own.