As part of the Design Thinking team at Zion & Zion, we are always seeking new methods and training to enhance our skills.

Indeed our Design Thinking team here at the agency has already been through design thinking programs at Harvard, Stanford and Emeritus, however, when we learned that the Nielsen Norman Group (NN/g), was offering a short course on design thinking, we decided to attend to see what perspective NN/g would have on the subject.

NN/g Design Thinking Course

Our favorite quote of the day came from Jakob Nielson, “Designers don’t try to search for a solution until they have determined the real problem.” This was the foundation of the course. What is your user’s pain point? Why does that matter? It is truly identifying this pain point that allows you to brainstorm innovative, breakthrough solutions.

In order to uncover a user’s pain point, NN/g took us through a series of structured steps, which is very characteristic of the group and their training style. Below are the steps to uncover a user’s pain point and determine the real user problem.

Understanding the User

First and foremost, you are not the user. Your preconceived ideas and biases should not be involved whatsoever when empathizing with your user.

Secondly, sympathy and empathy are two very different things. Sympathy is acknowledging another person’s emotional hardships. Empathy is understanding what others are feeling. There is a distinct difference and should be noted during this initial stage. If you notice that you start to make assumptions and/or jump to conclusions, stop immediately, clear your head, and ask with a toddler’s mindset: Why? Really try to get at the heart of why someone would act/react a certain way.

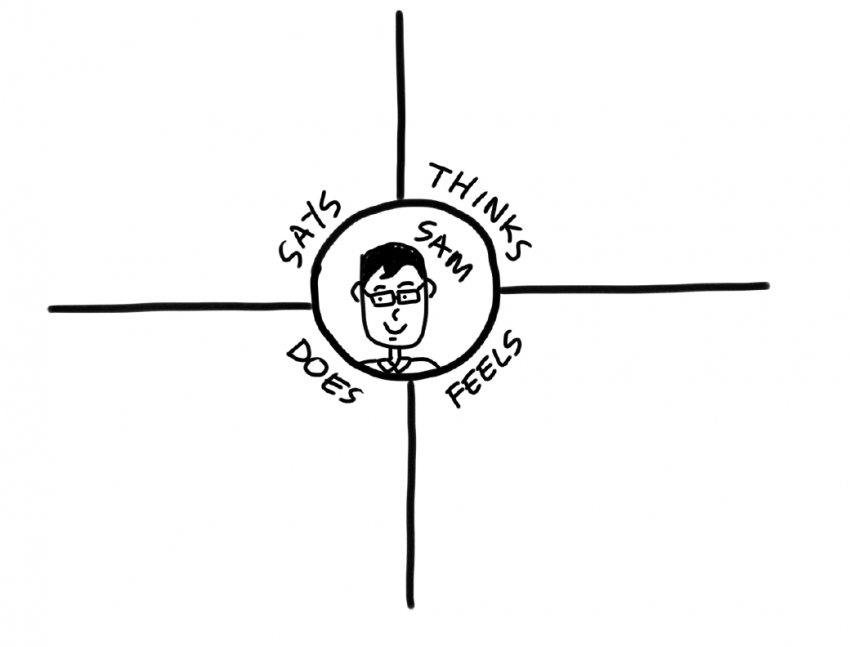

User Empathy Map

A user empathy map is a great tool to use when categorizing a user interview, diary, or any other correspondence. The map is divided into four quadrants: says, thinks, does, and feels.

The says quadrant is reserved for direct quotes from the user.

The thinks quadrant is a direct correlation to the says quadrant. The user says X, so they must think Y. This quadrant is left to mild interpretation, meaning you don’t have jump to huge assumptions. If the user says: “Do I really need to do this?” maybe they are thinking “I don’t feel prepared to do this.” It’s that simple.

The does quadrant are the actual actions the user does in order to complete their task at hand. Please note that this may not match up exactly to what the user says. For example, a user says they are not sure what to do, but then goes into a series of actions to get the job done, showing they did have an idea how to achieve the task at hand. The big takeaway here would be to understand why there was a disconnect.

The final quadrant is for notes about how the user feels. This is the quadrant reserved for leaps of assumptions because the user isn’t going to necessarily tell you exactly how they feel or dig deep.

Speaking of assumptions, one of the most valuable tools we learned about during this day-long conference was the parking lot. Yes, people use the idea of a parking lot all the time to avoid derailing meetings and discussions, however, this application is a bit different as it is applied here as a place where you can write questions and/or assumptions that you can test later. For example, you have interviewed your user and are filling out the user empathy map. You come to the feels section and assume that the user is afraid of failure because they are afraid of letting their parents down. Instead of arguing for the rest of the day with your team members about the validity of this statement, you can park the assumption in the parking lot and come back to it to verify the theory at a later day. This is a wonderful tool because it keeps the conversation moving, which is essential for design thinking. At the end of each day, you and your team will review what is in the parking lot and attach to-do’s for questions and/or assumptions. For example, your team member will be assigned to follow up with the user to ask more probing questions as it relates to their feelings about their parents and failure, i.e. tell me about a time when…, and confirm whether the assumption was valid or not.

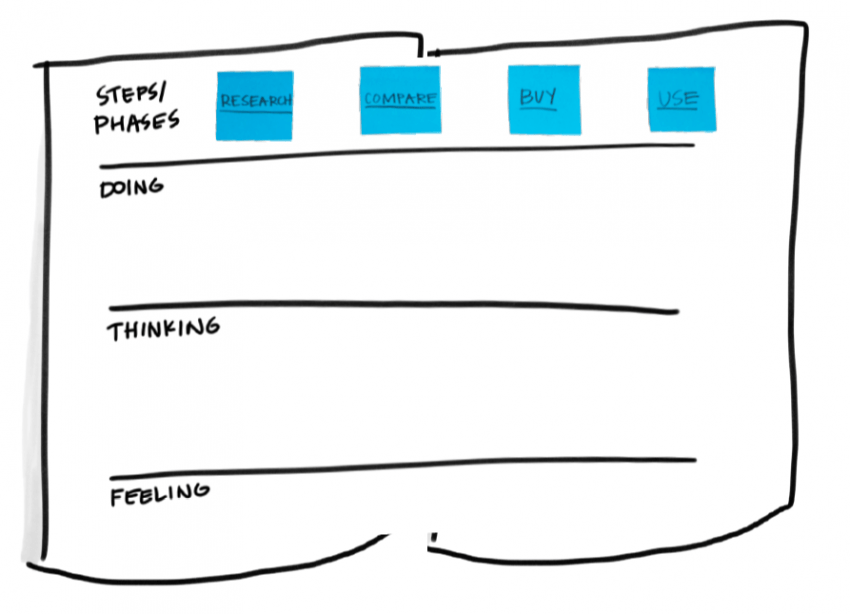

As-Is Scenario Map

Once you’ve completed the user empathy map, you’ll cluster you and your team’s thoughts into groupings with similar themes. From there, you’ll take each theme and map out as-is scenarios. This as-is mapping tool captures the workflow as it occurs today and helps you determine how your user accomplishes a specific task.

The map is divided by four “swim lanes” which include: steps/phases, doing, thinking, and feeling. The most common steps/phases typically include research, compare, buy, and use. From there, you take your notes from the does, thinks, and feels quadrants in the user empathy map and move them accordingly in each corresponding “swim lane.” Once the map is completed, you and your team will identify places during the process that your user experienced pain. Circle these areas because these will be the areas you’ll focus on to identify opportunities.

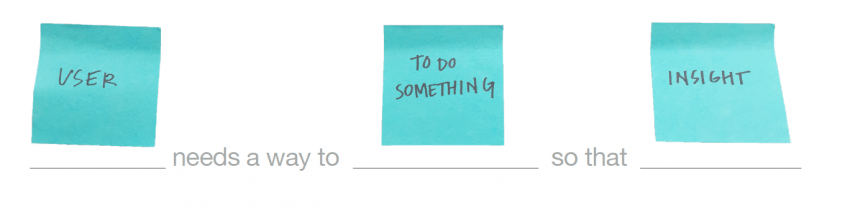

Creating a Needs Statement

Once your team has identified a few pain points, i.e. areas of opportunity, vote on which area to move forward with. NN/g recommends a democratic evaluation where each member individually votes with stickers and/or pen marks which the team can review collectively afterwards.

Once a pain point is selected, your team will need to write a needs statement. A needs statement is an actionable problem statement that launches your team into ideation, i.e. brainstorming. It is framed as the following:

A needs statement is NOT your solution, it’s a clear and concise way to frame the user’s problem. It should inspire the team and be actionable, not leave them with more questions. The goal of a proper needs statement is to identify and align around a point of view. If your needs statement is too broad and/or vague, go back to the drawing board. During this process, it is okay to move the “Insight” and “To do something” notes around until your team comes to a consensus. If your team gets excited about the statement and is inspired to start brainstorming around it, you’re probably in a good place.

Conclusion

Overall, the short NN/g design thinking course was valuable. Certainly not as intense as the Stanford and Harvard course and nowhere near as lengthy as the nine-month Emeritus program, but still a great learning experience for those that either want to enhance their design thinking skills or those just starting out in design thinking, that don’t have the resources to invest in something more comprehensive.